It’s that time of the year again, when anxiety, celebrations, jubilation and anticipation await all corners of our nation with the official release of the 2021 matric (Grade 12) results. This year’s official matric results came with its fair share of drama when the basic education minister, Angie Motshekga announced previously that, as per the new Protection of Personal Information (POPI) Act, the results would not be published on mainstream media as has been the norm for years in the Republic. Fast-forward to almost 72 hours before the release, after a court case against the department championed by Afriforum made its way to the Pretoria High Court successfully, the department had to abide by the court order and publish the results. Talk about a major U-turn when many, including myself, where relieved of the initial decision but alas, it is what it is.

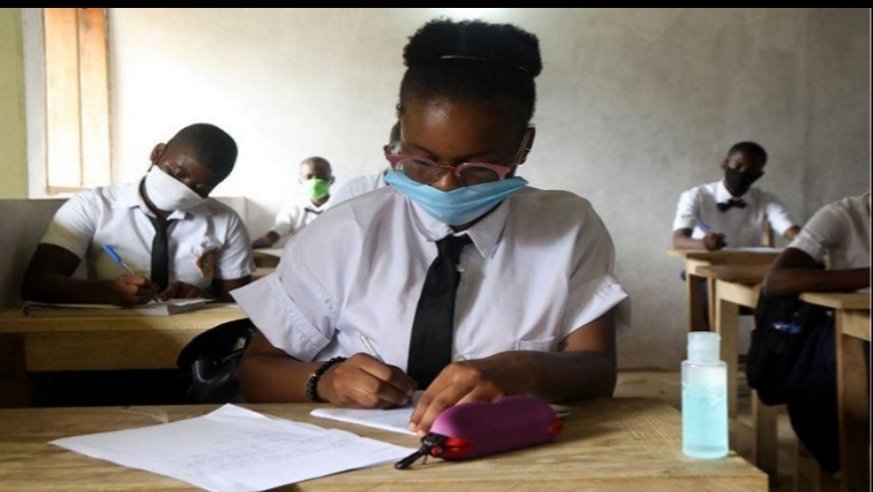

The class of 2021 are a special cohort, having went through school for two successive years under the global Covid-19 pandemic with its many restrictions imposed. It’s been two years of disrupted learning that has shaped our discourses to themes such as rotational, virtual and online learning to be the talk of the town. This hasn’t been an easy adjust or adapt to many of our hard working learners and teachers out there. School times have been interrupted due to confirmed cases, for deep cleaning and contact tracing to mention some of the disruptions that have been caused. Yet, thousands, pulled through this hurdle.

With jubilation as the order of the day, I would like to move the attention away from the top achievers for a while to groups of individuals who have proven all theories wrong. As someone who also comes from a township public schooling environment, I can attest to the hard work that is put in by both learners and teachers where the context offers any reason in the book, worthy of deeming success a wishful act. Some schools have top of the range facilities, equipment and resources to enable effective learning and teaching to take place. You have schools in our land that lack proper basics such as decent sanitation, shelter to cover as roof for learners and teachers during those times when the weather does not play ball, proper classes, sports grounds, you name them. How these are still a fabric making up our society, 28 years after democracy is still a worrisome concern.

Some learners don’t even have teachers, or the most passionate who are invested in the job – teaching.

I was fortunate to be in a public school system where although there was a definite lack of resources, which could have enabled me an easier path towards success, I am a firm believer that what you work so hard to learn and achieve by your own efforts and with whatever help you can get from those around you, you always treasure. It’s never about luck. It’s commitment, determination, hard work and time invested, lots and loads of it. With the many hurdles facing our public schooling system, I am glad that there is some progress that continues to take place, though it can improve and get much better with time.

Our focus and fuss over the matric results is not an ideal matter, granted, they too (results) are worth mentioning but there is often more to it than simply the figures. What I am encouraging though, is a shift in our thinking, focus and perspective where matric results are concerned. The main focus is always on the numbers, the overall percentage and the basic education department always having its eye on putting across an ‘improvement status’ of the results year on year. While we’re also at it, why is it always the independent schools who receive their results first? Maybe another number’s game answer? And there is always this huge difference between the two types of schooling (private and public) and I would not want to venture into those distinct differences that define the many structural differences still existing.

Now to where the focus is:

1. Overall pass rate.

Why are we all so obsessed with this from a surficial point of view and not drill down deeper? I believe that the pass rate will progressively go up, year-on-year and will not drop. If it drops, education officials need to account for it and they would not want to be in that situation. Now the question I have is, will it ever get to 100% and would that help solve all the educational challenges and questions around the system as a whole and is that even feasible? What’s interesting to observe is how the private school overall pass rate always hovers around the 90 to 99% mark year-on-year with a small portion that never makes it. Many use this as a litmus test to judge how well one system performs over the other but drilling down deeper beyond these figures is much more important. This year’s group attained a 76.4% up 0.2% from the previous cohort’s overall percentage.

2. Top achievers.

Granted, in every year, there will be top performers that need to be recognized and I understand the reasons behind it and we ought to rightfully celebrate them. But Top performers should not be our sole focus as we reflect on the results particularly those coming from privileged schools. I believe that there is more to top achievers than that.

3. Top performing provinces.

The push for good results often leads to the rankings, where MECs are now in competition over which province is the best over the other. Issues affecting provinces from achieving their best and lessons that top performing provinces can share with the rest of the provinces, should be in the spotlight, not which one has performed the best as compared to the rest as the sole focus. WE need to move away from the rankings and countdown or is it up?

4. Top performing schools.

No two schools are the same and the fact that we have public private schools in the mix, adds a unique layer to the conversation. There is that constant pressure to gun for ‘top performing schools’ when parents seek to enroll their children into good schools and there are a number of salient factors that the overall percentage fails to uncover such as the quality of learning and teaching, support from teaching staff, a school’s discipline, easy access to learning and teaching aids to further enhance education within a school. The figures don’t clearly paint a good picture with regards to that, they can only be used to infer but that’s as far as it goes. The sooner we move our focus away from the overall results, the easier it will be for us to delve deep into issues that need to be dealt with in order for our education system to thrive.

Now, to where the focus should be:

1. Learners who make it against all odds.

In our celebrations, there will be learners who won’t make the news yet have been able to succeed against limiting circumstances. Those are the learners who in my books, deserve the credits. Learners who will have achieved greatness where conditions around them such as a school without access to resources and proper facilities to enable them to succeed, deserve all the credit that they can get. Many will not boast distinctions but overall good passing grades, to those (many of those, I am certain) I say well done and I salute each and everyone of you. This is where our focus should be.

2. Publish schools that have shown the most improvement.

Yes, the top performing schools are important but equally so are those schools who will have moved from the bottom of the barrel status to the top-end as a result of interventions that they would have implemented. Let’s publish more of those schools in mainstream media and let’s make a big fuss over those, shall we? There is always a glimmer of hope where there is incredible adversity. Let’s bring it back to aspects like these.

3. Bottle neck & The alternatives: Accounting for the numbers lost in the schooling system.

A big reality now is that of the number of the matric class of 2021 that succeeded, there is a significant proportion of those that do not make it. This year, 23.6% of the learners which is 897 163, the total number of candidates who registered for the NSC exams, of which 735 000 sat down and wrote, did not make it. Another reality with the results is that year-on-year, these results only reveal a fraction of the initial number of learners who got into the education system 12 years ago. In fact, the 76.4% accounts for 54% of the children who entered the system 12 years ago. Roughly 1.5 million children entered Grade 1 in 2010, only a third of them, 560 000, successfully matriculated 12 years later. These are statements echoed by political columnist Lindiwe Mazibuko on her piece from The Sunday Times titled ‘Why celebrate when a million kids dont make it to matric each year?‘ (see full article on the references). There are a number of children who are lost and are unaccounted for throughout their schooling career and this is a cause for concern. Educational research specialists ought to study the phenomenon and provide feasible reasons to account for this and to map out solutions towards curbing this. It’s a reality we must not shy away from.

4. Future plans for these children.

In the midst of the celebrations, the reality is that not all our institutions of higher education such as Universities for instance can accommodate all those who made it. Granted, not all the learners would have ambitions to study at Universities but there needs to be conversations around the next phase for these learners and how they will be accommodated in the higher education and training department as a whole – what’s next for them? What are the options available? The options available for those who did not make it, need to be easily available and offered as a feasible and encouraged alternative. There also is a need for therapy and psychological assistance to be offered to prevent suicides and assist learners in planning a better future for themselves. These services need to be easily available for the learners to make good use of. Another conversation we need to be having is the high unemployment rate in the country, particularly in young people who have graduated. Statistics (according to The Daily Maverick) reveal that 40.3% of those unemployed graduates are aged up to 24 years while 15.5% of them are aged 25 to 34 years. This is a worrying trend and needs to be addressed to curb a further uptake of matrics who may possibly suffer the same fate if necessary interventions are not made.

I take this opportunity to congratulate the many learners who managed to overcome this hurdle and to the hardworking teachers, tutors, school principals and educational stakeholders who each played their part in the success of the 2021 matric class. And especially to those learners who managed to succeed when all odds were against them, the schools that showed a tipping point by showing an improvement in their results year-on-year, no mater how small. There is a number of issues with our educational system however, any small change and progress needs to be acknowledged and shortfalls need to be discussed and strategically managed to map a feasible way forward for the future of our children. We all have an indirect role to play in this.

References

Calling all unemployed and underemployed graduates: Make your voices heard on 1 November